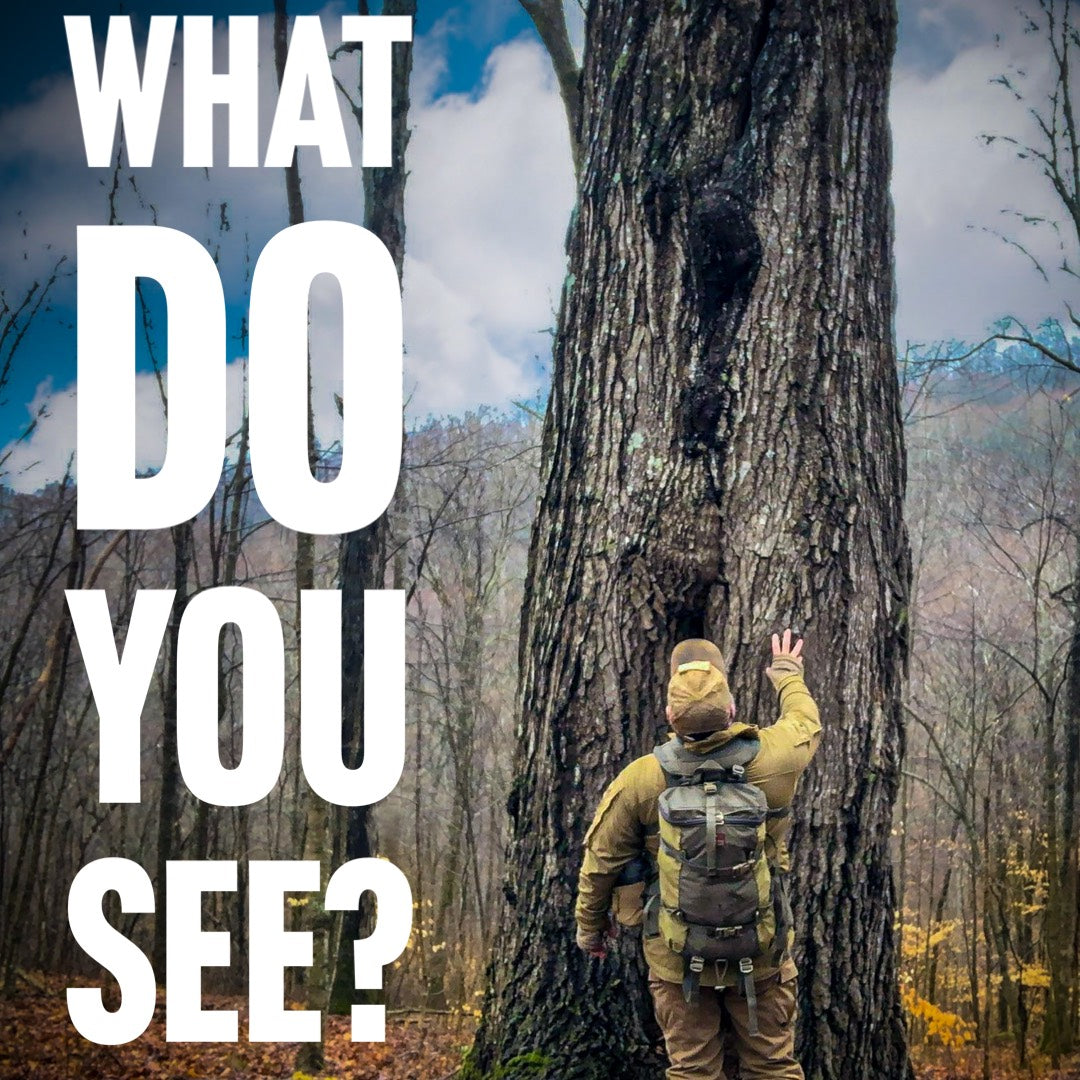

What do you see?

Editors Note: This blog piece was written by NRS Cadre member, Mr. Eric Comley.

When you are looking at a tree, what do you see? How do you denote differences? The commonplace response is to look at the leaves, needles, or scales of the tree and make a best guess, but the importance of tree identification within those finite characteristics of an individual species can make all the difference in the world when you are lost, looking for water, looking for food, looking for something that looks at that tree for food, building a shelter, or just on a stroll through a local forest. The tree before me, properly identified, could answer a lot of questions or temporarily subside some ills to make you more comfortable in the woods.

First of all, look at trees like your friends. Nothing weird and there is no expectation for you to have conversations with your ash (Fraxinus sp.) or oak (Quercus sp.) tree friends, but the effort should be made to know who you are in a crowded room with, or, in this case, a forest. When my friend Patrick is around, I recognize him by facial features, body shape, gait, voice, and a whole host of designated characteristics that make him uniquely Patrick. The same idea can be placed on trees.

We have a tendency to see a single characteristic of a tree and make a generalization about what may actually be standing in front of us. If I see a pair of glasses on a table, and I know Patrick wears glasses, I can’t assume they belong to Patrick until I see the glasses in his hand, or, even better, on his face. If I see needles on a tree, I can generalize it may be a pine (Pinus sp.), but, if I take the time, spend time around that tree, learn a little bit more, I may learn it is an eastern white pine (Pinus strobus). Proximity doesn’t give me that information, but careful study, character recognition, possibly using a key, or walking with a knowledgeable person will. From there, I see fascicles (tufts) of five needles, wagon wheel branching pattern up through the tree, and

a magnificently straight tree with a variety of timber functions. In addition, as I learn more, I see high concentrations of Vitamin C, pine resin for fire, and pine nuts tucked into the cones. Pine nuts may be a food source for me or they may be a food source for something else that may also feed me.

You’re thinking, “A pine is an easy one. What about an oak?” Agreed. Those occasions when you happen to have a set of identical twins as friends definitely increases the likelihood of mistaken identity or the family in your community that has five of six kids and how you separate them out from one another. Name, age, hair color, grade in school, or whatever self-designed dichotomous key system you apply to those situations, but you learn. For trees, it is simply looking at leaves (if available), fruit, flower, where it may grow in the landscape, bark, buds, leaf scars, or something you consistently see in those species. Oaks (Quercus sp.) are a perfect example. There are 24 different oak trees in Kentucky (14 red oak subspecies and 10 white oak subspecies), so they are somewhat easily divided by the shape of the leaf. If leaves aren’t available, we go to habitat, buds, bark, acorns, and even acorn caps. Each of those oaks will tell you and potentially provide you with something unique for your use in the outdoors. If I find myself in a stand of chestnut oaks (Quercus montana), I may be at or moving toward the top of a ridge in relatively acidic soils, but, if I find myself in swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor), I may be knee deep in a swamp or wet forest. From a navigation standpoint, understanding the trees around you may assist you with finding yourself on a map.

Being situated in a state (Kentucky) with more than 120 different species of trees, your “friend” group grows substantially and your effort, if you choose to understand the forested areas, becomes exponentially more challenging. Not to bring social media too much into this, but I have a lot of “friends” on Facebook, but my core group of people I pay attention to or have conversations with is much smaller. My point is, while there are 120 species in these borders, some of those are rare, endangered, or just too far away for me to recognize each time we meet. Those commonplace trees display those unique traits to make them easier to identify, even without the benefit of leaves. For example, black walnut (Juglans nigra) has a unique monkeyface leaf scar, yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) has a duck-billed terminal bud, and American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) has a varying colored bark, but it is primarily white. All of these characteristics can be used as individual identifiers, but, to be thorough, someone should always look for additional items (bud, bark, habitat, fruit, flower, smell, leaves) that will solidify an identification.

Essentially, walking into a forest without “wanting” to know the tree life around you is taking one more tool away from you to use. While the process of identifying trees can be easy, the effort should always be made to learn what makes each species unique and, from there, what makes them ultimately useful in a number of situations. Simple dichotomous keys, field guides, and a wide range of knowledgeable people can provide simple instruction to improve your mindset while in the woods, develop skills for your or your group safety and survival, and enjoy the presence of some new and old dendro-friends.

Leave a comment